Page last updated: August 6, 2017

All pages copyright © 2017 by Alison K. Brody

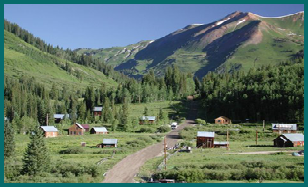

My research explores how plant interactions with multiple species (including mutualist pollinators and antagonist seed predators, herbivores, and nectar robbers) affect flowering plant ecology and evolution of floral traits. Although we generally think of flowering traits evolving strictly in the context of plant interactions with pollinators, antagonists exert important selection on floral phenotypes as well. I’ve conducted most of my work at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory near Crested Butte, Colorado.

MULTI-SPECIES INTERACTIONS:

ECOLOGICAL AND EVOLUTIONARY CONSEQUENCES

Gothic, Colorado

Effects of mutualists and antagonists on the persistence of females in gynodioecious populations of Polemonium foliosissimum.

SEX UNDER SIEGE

I’m intrigued by the links between floral mutualists and antagonists in the stability

of plant mating systems. Along with colleagues Bob Dorsett and former PhD student,

Gretel Clarke, I’ve been examining those links in a gynodioecious plant, Polemonium

foliosissimum (Sticky Polemonium). In gynodioecious plants most individuals are hermaphrodites

and others are female (having lost male function). These plants provide an opportunity

to examine extreme phenotypic differences in floral traits and the role of species

interactions in trait selection and maintenance of gender morphs. Most recently,

I’ve gotten interested in how pollen thieving flies affect gender expression and

functional sex-ratios in Sticky polemonium.

I’m intrigued by the links between floral mutualists and antagonists in the stability

of plant mating systems. Along with colleagues Bob Dorsett and former PhD student,

Gretel Clarke, I’ve been examining those links in a gynodioecious plant, Polemonium

foliosissimum (Sticky Polemonium). In gynodioecious plants most individuals are hermaphrodites

and others are female (having lost male function). These plants provide an opportunity

to examine extreme phenotypic differences in floral traits and the role of species

interactions in trait selection and maintenance of gender morphs. Most recently,

I’ve gotten interested in how pollen thieving flies affect gender expression and

functional sex-ratios in Sticky polemonium.

Theory tells us that female fitness must be significantly greater than that of hermaphrodites to compensate for the loss of male function. Are female fitness advantages accrued through enhanced pollination? A reduction in seed predation? How much does the sex-ratio of the population and/or phenological differences among genders matter to female and hermaphrodite reproductive success?

Since 2001, I have been exploring the role of subterranean termites as ecological engineers of savannah grasslands in East Africa. Through their mound-building activities, termites generate habitat heterogeneity that, in turn, supports a diverse community of plants and invertebrates. In collaboration with Dan Doak, Todd Palmer, Kena Fox-Dobbs, Rob Pringle, and Charles Warui, our work has revealed that termites are significant drivers of plant and invertebrate species abundance, co-occurrence, and reproductive success, and their effects scale up from populations to ecosystems. Our work has been conducted in the black cotton soils at the Mpala Research Center, near Nanyuki Kenya.

When keystone species collide: effects of termites and herbivores on biological diversity in East African savannas

TERMITES - ECOLOGICAL ENGINEERS

Interactions with pre-dispersal seed predators, nectar robbers, herbivores, and pollinators.

IPOMOPSIS AGGREGATA - “SCARLET GILIA”

One of the focal species of my work is the monocarpic perennial plant, Ipomopsis aggregata—commonly known as “scarlet gilia”. In various collaborations with Diane Campbell, Rebecca Irwin, Mary Price and Nick Waser, I have examined a suite of questions about the simultaneous effects of pre-dispersal seed predators, nectar robbing bumble bees, deer herbivores, and hummingbird pollinators on floral traits and the long-term, multi-generational success of scarlet gilia.

One of the focal species of my work is the monocarpic perennial plant, Ipomopsis aggregata—commonly known as “scarlet gilia”. In various collaborations with Diane Campbell, Rebecca Irwin, Mary Price and Nick Waser, I have examined a suite of questions about the simultaneous effects of pre-dispersal seed predators, nectar robbing bumble bees, deer herbivores, and hummingbird pollinators on floral traits and the long-term, multi-generational success of scarlet gilia. Effects of Mycorrhyizal fungi on floral trait expression in blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum)

BELOW & ABOVE GROUND IN THE BLUEBERRY PATCH

The association between mycorrhizal fungi and their host plants is an ancient one

and, most often, mutualistic. Mycorrhizal fungi gather nutrients from the soil in

exchange for photosynthetic carbon and often affect their host plant’s resource budget.

Although their role in nutrients acquisition, drought tolerance and tolerance of

heavy metals has been long-established, we are only beginning to discover the ways

in which these fungi affect host plant interactions with aboveground mutualists such

as pollinators. I am interested in how mycorrhizal fungi specific to members of the

Ericaceae (called ‘ericoids’) affect flowering traits and floral rewards important

to pollination and plant reproductive success in highbush blueberry. With colleagues

Jeanne Harris, Steve Keller, Taylor Ricketts, and Leif Richardson, I am exploring

the questions: How important are ericoids to floral traits and rewards? How specific

are the interactions between the fungal community that inhabits blueberry roots and

trait expression in their hosts? How important are mycorrhizae to phenotypic variation

and selection on traits formerly assumed to be under direct selection by pollinators?

The association between mycorrhizal fungi and their host plants is an ancient one

and, most often, mutualistic. Mycorrhizal fungi gather nutrients from the soil in

exchange for photosynthetic carbon and often affect their host plant’s resource budget.

Although their role in nutrients acquisition, drought tolerance and tolerance of

heavy metals has been long-established, we are only beginning to discover the ways

in which these fungi affect host plant interactions with aboveground mutualists such

as pollinators. I am interested in how mycorrhizal fungi specific to members of the

Ericaceae (called ‘ericoids’) affect flowering traits and floral rewards important

to pollination and plant reproductive success in highbush blueberry. With colleagues

Jeanne Harris, Steve Keller, Taylor Ricketts, and Leif Richardson, I am exploring

the questions: How important are ericoids to floral traits and rewards? How specific

are the interactions between the fungal community that inhabits blueberry roots and

trait expression in their hosts? How important are mycorrhizae to phenotypic variation

and selection on traits formerly assumed to be under direct selection by pollinators?